Early in the morning on April 21, 1955, policemen stood outside the locked door of Otakar Švec’s apartment. Friends – those he had left – had not seen or heard from him in weeks. His career’s crowning achievement had just been completed and was ready to be unveiled: a 51-foot-tall granite statue of Josef Stalin, the largest depiction of him in the world. It was a major event, and Švec was conspicuously absent. Why wasn’t he there?

This man’s fate is one of the many mysteries from the Czechoslovak communist era. Švec was a successful sculptor who entered a competition that all artists were obliged to participate in. The newly established communist government sought the best proposal for a new statue celebrating their beloved figurehead. The winner would be generously rewarded and would earn the honor of building a statue so tall, on a hilltop so high, that the communist prime minister declared with joy that Stalin would be seen from the city of Cologne.

Even for a statue of such height, Švec’s submission stood out. All 60 submissions featured Stalin standing alone except his. Švec envisioned the communist leader at the front of a line of proud and hard-working members of the socialist society: a factory worker, a scientist, a soldier from the Red Army, and a farmer from the collective, sickle in hand. The piece portrayed a central ideal of their new socialist society. Members of the various social classes would stand together equally. This was the chosen design, but its myriad problems meant it would take five and a half years to finish.

To start construction, several things needed to be done first. The local soccer team’s newly finished stadium on the hilltop needed to be demolished. The material of the statue needed to be chosen. Much to the sculptor’s dismay, the committee decided on granite, a notably unworkable stone. But they chose it for its durability, as the statue was meant to last forever. Thus, the ground needed to be reinforced for what would be an exceedingly heavy sculpture – 235 tons of granite. Stalin’s head alone would weigh 52 tons, the equivalent of about 10 African elephants. After all problems were settled, construction was continuously postponed and eventually began in February 1952, two years after the initial proposal.

Then more problems came. Švec was asked to redesign the sculpture several times. Make Stalin larger so he wouldn’t be overshadowed by the others, they said. Replace the abstract individuals behind him with specific heroes from the communist party. After this critique, Švec decapitated the disputed figures on his model and stormed out of the studio. He didn’t return for two months.

Two major deaths occurred in the artist’s life before the completion of the sculpture which likely had a role in his own tragic end. One was global and the other was deeply personal.

The first came in March of 1953. Josef Stalin was found unresponsive and incontinent on his bedroom floor, apparently having suffered a cerebral hemorrhage. Attempts to lower his blood pressure led to leeches being applied to his face and neck. No modern nor medieval treatment sufficed, and he died on the evening of the 5th.

His death was announced, his body embalmed, and hundreds of thousands came to see him. The affair was so chaotic that several members of the crowd died in a crowd crush. Stalin was beloved. He had successfully created a cult of personality around himself such that he could do no wrong. It would still be a few years before Khrushchev delivered his ‘secret speech’ where the horrifying truth of Stalin’s crimes came out. But perhaps his death alone was enough to cast a pall upon the project in Prague on Letna Hill.

The second death was that of Švec’s beloved wife, Vlasta. A beautiful young woman prone to drinking and recklessness, their relationship was marred with frequent fights over her way of life. At one point, Švec had had enough and moved out. Shortly after this, on April 20th, 1954, Vlasta took a handful of sleeping pills washed down with too much alcohol, left the gas stove running, sat down on the sofa, and faded away.

Taken together, these two events must have changed things drastically for the artist. Understandably, Vlasta’s death was a shock. He blamed himself for her suicide since he had refused to move back in with her even when she threatened to poison herself in his absence. Stalin’s death was more remote, perhaps, but it defined a new era. As the sculpture approached completion, we can suppose these events were top of mind – the death of the man he was immortalizing in stone, and the death of the woman he loved. Acquaintances of his from that time recalled how he was afraid of old age. “Vlasta did well to poison herself,” Švec said, “at least she doesn’t grow old.” Completing a major, career-defining work can make one think about their own mortality.

The morning they came to look for the artist, police had to force the door open. A blanket was lying on the threshold to seal the gap. When they entered, the smell of gas and decomposing flesh hit them like a bus. Upon the very sofa where Vlasta had died sat Otakar Švec, having taken his life the same way.

The note he left read as follows:

“I am leaving to my wife Vlasta and bequeathing all my property, including the last payment for the Stalin monument in Prague, to the soldiers blinded in the war. I do so after mature consideration and I wish it to be carried out as well… I am writing this will without witnesses so as not to draw attention to myself. Take the amount for a simple cremation from the money found with me, let the rest be paid from my remaining account for the Stalin monument.”

The government forbade the papers from printing a word about it. They did not want the public to associate his suicide with the monument. The silence only caused the rumors to spread faster. The story that developed at the time described a man tortured to death by his connection to a monstrous monument. Nearly 70 years later, it is clear that the story is not so simple. A sculptor of public monuments must be aware of his function, keeping the memory of our heroes alive after they die. For someone fearful of old age and death, the act might be an attempt to claim some of that immortality for themselves.

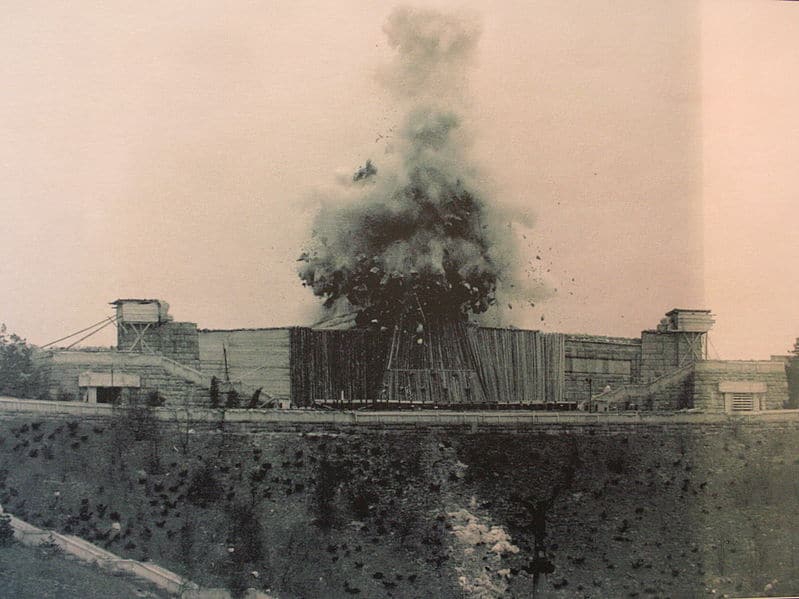

The bitter irony of this story is that the granite monument which was built to last forever didn’t make it 8 years. After Stalin’s crimes were revealed, the Communist Party in Moscow decided to remove Stalin’s mummified body from the mausoleum on the Red Square in 1961, and the next year in November 1962, the Stalin monument on Letna was blown to bits. Two tons of explosives, two thousand detonators, and Švec’s most important work was eviscerated.

Today, upon the hill, we see a different work of art. A 75-foot tall, bright red metronome slowly sways from left to right. Built by Czech sculptor and professor Vratislav Novák, it is called Time Machine and symbolizes the inexorable passage of time. Placing it on the pedestal where Stalin once stood is meant to serve as a reminder of the past which time slowly carries us away from.

To visit the monument which locals still call ‘Stalin’, you will want to take a tram to the stop “Čechův Most,” or simply take the 15-minute walk from the Old Town Square. From here you can walk up the stairs to the top of the hill. On a nice day, you can bring some food or get a beer at the nearby beer garden and watch the skateboarders ride around the platform where Stalin once stood. Sitting below the metronome’s arm, you can take in Prague’s labyrinth of architecture, let the time pass, and maybe even come to terms with your own mortality. Or just enjoy the view.